Aktuelle Promotionen

Teledyne LeCroy-Application Note - Power-3 - The Fundamentals of Power - Three-Phase Sinusoidal Voltages (E)

In The Fundamentals of Power Part II , we briefly covered the basics of single- and

three-phase AC power systems. Single-phase systems, as we've noted,

comprise a single voltage vector with a magnitude (in VAC) and a phase

angle. Of course, a three-phase voltage consists of three voltage

vectors and three phase angles. This installment will go on to describe

three-phase AC voltages in similarly brief fashion.

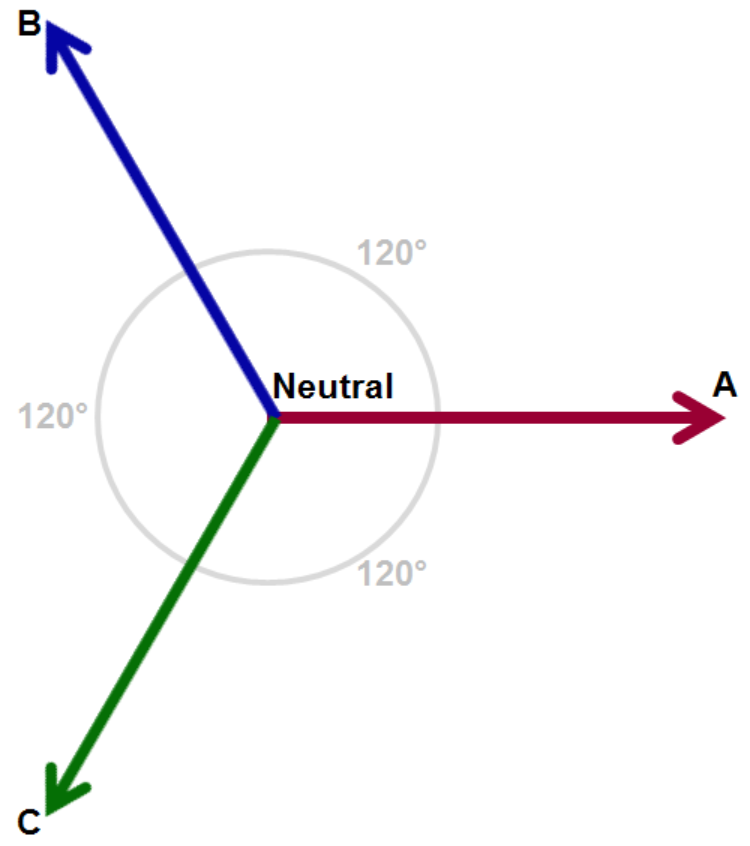

As mentioned above, three-phase AC sinusoidal

voltages consist of three voltage vectors (Figure 1). By definition,

these vectors are "balanced," being separated by 120° in phase, and

being of equal magnitude. Moreover, the sum of all three voltages is

equal to zero volts at the central neutral point.

| Typically, the three phases are designated A, B, and C. However, you may

see other conventions used for these designations, such as 1, 2, and 3;

L1, L2, and L3; and R, S, and T. |

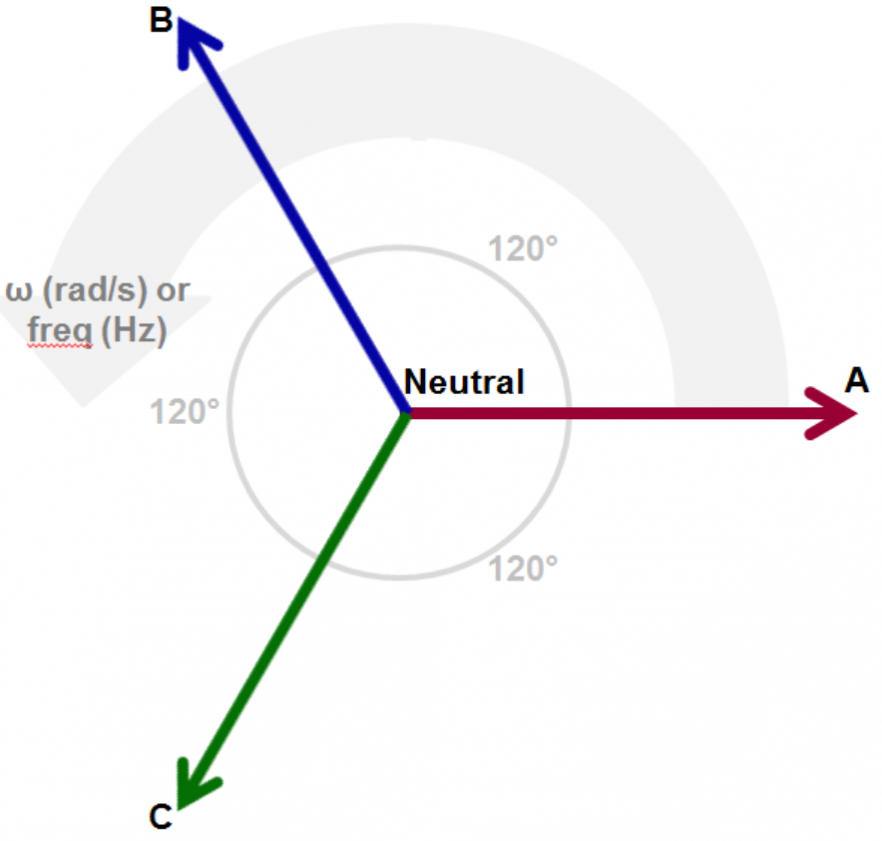

| Like single-phase voltages, three-phase AC voltage vectors rotate at a

given frequency, which typically is 50 or 60 Hz for utility-supplied

voltages. As they rotate together, the vectors maintain their 120° phase

separation (Figure 2). The voltage is generated by the utility using a

rotating machine, i.e., a "generator." The generator uses a rotating

magnetic field to induce a voltage in its stator. And again, like

single-phase voltages, the resulting voltage vectors have magnitude and

phase values. The resulting time-varying, "rotating" voltage vectors appear as three sinusoidal waveforms. They are separated by 120° in phase and are of equal peak amplitude. |

The voltage value is calculated as: Vx * sin(α), where Vx is the magnitude of the phase voltage vector and α is the angle of rotation (in radians).

There are a variety of reasons for using three-phase AC voltage:

- It's more efficient to generate power with three-phase generators

- It's easier to manufacture high-power transformers and motors

- Superior control capabilities for low-power motors

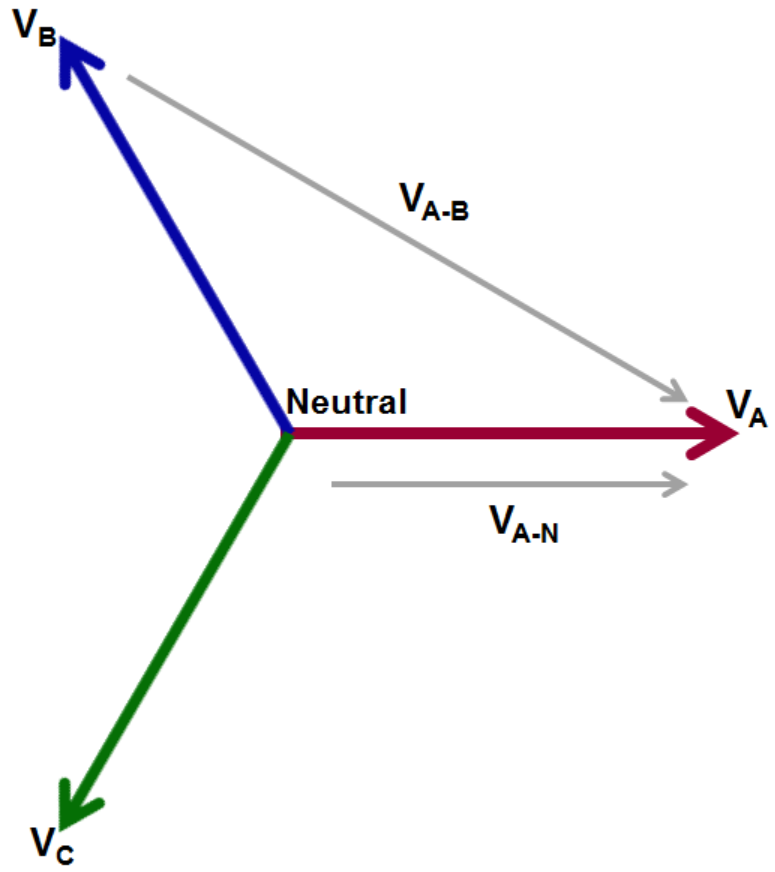

In three-phase systems, voltage can be thought of, and measured, in two ways (Figure 3). One way is to measure line-to-line, or phase-to-phase. Such measurements may be referenced from VA to VB (or VA-B for simplicity), for example. The second possibility is to measure line-to-neutral; for example, from neutral to VA (or VA-N for simplicity). For such measurements, of course, neutral must be both present and accessible.

Note that the line-to-line vectors are longer than the line-to-neutral

vectors. Thus, magnitudes of line-to-line voltages are typically larger

than line-to-neutral voltages. It's more common to probe and acquire

line-to-line voltages, because while a neutral point may not always be

present, there will always be the three lines. Also, line-to-line

measurements may be converted to line-to-neutral values and vice versa.

The differences between them boil down to a 30° difference in phase and a

magnitude difference of √3.

Next time, we'll look at the ways in which three-phase connections can

be made as well as more details of line-to-line and line-to-neutral

measurements.

This is an application note from Teledyne LeCroy

Tameq Schweiz GmbH

Im Hof 19

CH-5420 Ehrendingen

Tel: +41 56 535 74 29

Fax: +41 56 535 94 97

Mob.: +41 78 704 56 51

Email: mail@tameq.ch